Thirty years of students on-screen

Looking back at sleazy stereotypes, troubled teens and obsessive over-achievers

Whether it’s the American high-school lockers, the British school uniform, or the universally relatable social awkwardness - there’s a certain something about the classroom setting in films that just pulls me in straight away. It could well be the past five or so years that I’ve spent being an English teacher: but it’s probably the neatly-tucked-away part of me that weirdly misses the green ticks of approval on a worksheet.

I’m nearly 25, but even in the past decade alone, there’s been a massive shift in the perception of what school is, what a good student is, and what teachers should be like. In the decade before that, I wasn’t old enough to think about it and in the decade before that, my parents were probably thinking about how times had changed.

Education on film has been a tricky one in recent years. Miller’s Girl most recently stirred the pot for depicting an incredibly uncomfortable potential student-teacher romance with May December hot on its heels, based on the true story of the student-teacher relationship between Mary Kay Letourneau and Vili Fualaau (albeit fictionalised and adapted for the film). A little further back in the late 00s and early 10s, films like Detachment and Half-Nelson depicted less romantic but still problematic connections between students and their teachers - breaching what we would confidently call ‘duty of care’ in today’s classroom.

Between the 2010s, the 2000s and the 90s, the perception of students has gone on an incredibly long-winded ride. The work of the 80s in Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club and Heathers aided the normalisation of students being depicted as desperate to grow up and become ‘adults’, seemingly only initiated through the realm of sex and romance. Skip through the early 90s past films like Dazed and Confused, Angus, and Clueless, and you get to the golden year of 1999: home to iconic films 10 Things I Hate About You, Cruel Intentions, American Pie and our main before-the-second-millennium star, Election, starring Reese Witherspoon and Matthew Broderick.

If you’re not interested in reading about this film or my views, I’d advise sparing thirty seconds and having a quick look at my Letterboxd review here. That ought to summarise my feelings quite aptly. If you’re sticking with me, let’s start with my unfortunately very confident belief that pre 2000s, there really was not much media representation in favour of the student. Tracy Flick, played by Witherspoon, is very clearly portrayed as an annoyance and an obstacle that greatly-loved Jim McAllister feels the need to sabotage.

Why? Well, because he is sexually tempted by her.

As previously mentioned on The Amateur’s Take, I am an emotional viewer. I do not take abuse, assault or violence lightly in films, especially when trivialised. Needless to say, I was quite appalled to learn that Election is still hailed as an iconic high-school film and also (yes, this is true) holds the title of Obama’s favourite political film. Strip away the odd comparisons of Flick to Hilary Clinton, the charm of the Metzler siblings Paul and Tammy and the unbelievably odd sub-plot of extra-marital affairs and you are left with a film that treats the student as an opportunity, as a temptation, and as an adversary.

Flick is not alone: the aforementioned Metzlers are also stereotyped as selfish and somewhat insecure. It seems that students are viewed as sponges, absorbing whatever their teachers tell them without question, but also used as punching bags, for short-sighted teachers to ragdoll around. The film’s only redemption of this damning characterisation is the recurring trope of the stream-of-consciousness narration of each student, allowing their own voices to be heard in ways untouched by adult words. Having said that, it is eerily clear at the beginning of the film through Flick’s recollection of her experiences with Dave Novotny, now ex-teacher after grooming Flick, that she is simultaneously being presented as a naïve young girl, but also an annoyance of a woman, thanks to McAllister’s own inner monologue.

Our poor student Tracy Flick, plagued by the pursuit of a student presidency and the promises of a predatory teacher, is used as a scapegoat for McAllister’s problems.

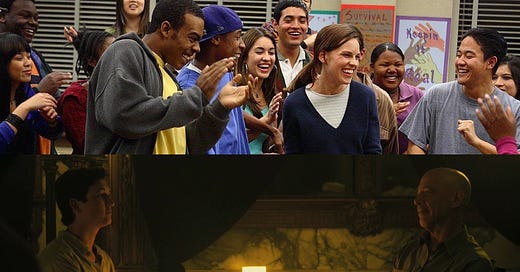

Unfortunately for the majority of the 2000s, this scapegoat continues, limiting the student’s story to one of popularity struggles and appearance concerns. As the story began to become too played out and repetitive, filmmakers and screenwriters turned to the missed stories of the past to tell new tales about the student. Case in point: Freedom Writers. A story born in the mid-90s after the Rodney King riots, based on a book written by the students and teacher portrayed in the film, I’d argue that 2007’s Freedom Writers marked a turning point for student storytelling: their cultural significance and their individual stories were beginning to be told in place of the superficiality of the past decade.

Often referred to as a white-saviour movie (and I agree), Freedom Writers took the misgivings of the previous ten years and dug deeper into the student stereotype, lifting the blanket of delinquency and revealing how students are subject to inequalities beyond their control, often enforced by the teachers assigned to mould them.

There’s a great deal of eye-opening takes in Freedom Writers - if you live under a rock or in the year 2005.

The overwhelmingly inaccurate perception of the students in Erin Gruwell’s class as “just criminals” and “not activists”, or as woefully “disengaged and disrespectful” is challenged for maybe the first time on-screen, allowing students to not be seen as a burden on the education system but in fact, burdened by an education system that doesn’t work for them. Of course, nearly twenty years later, there is a element of cringe in Hilary Swank’s use of AAVE to connect with students like Jamal and Marcus, who (rightly) criticise her for trying to “teach rap” to them - a painfully ironic sight. Although it feels at times like the film tries to assert Gruwell herself as changing the way students are viewed, it’s undeniable that the film was impactful in creating a narrative that “teenagers deserve to be listened to” - which is a whole lot more than Election did.

Through scenes such as the ‘line game’ that Gruwell uses to unify her class, or moments where she buys books for the students who are in awe that they’re “brand-new”, it becomes achingly apparent that although perceived to be a cultural problem, the students from minority ethnic backgrounds tend to be the most culturally bankrupt. In this vein, Freedom Writers begins to address the severe lack of ambition, individuality and determination associated with the story of the student on-screen. This trend continues in films like Precious, maybe even The Blind Side, and of course, Whiplash.

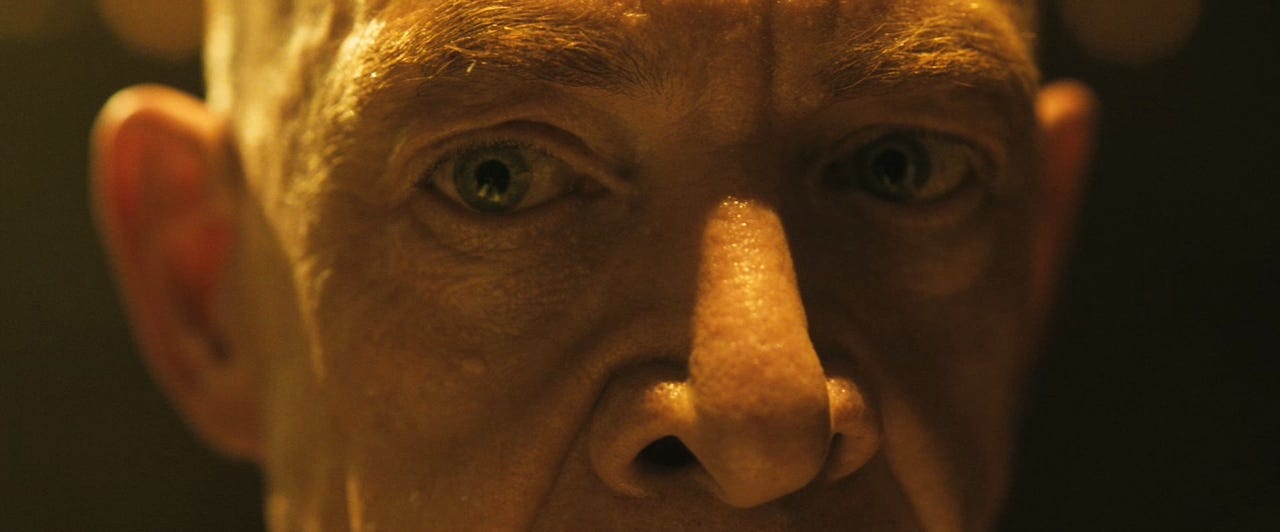

Admittedly, it is shameful that I have only just watched Whiplash for the first time, a whole decade after its release. (And just in time for its 10th anniversary re-release!) For the purposes of this piece however, it was perfect timing. With Whiplash, Damien Chazelle broke past all that was remaining of the Tracy Flicks and Erin Gruwell’s students to create Andrew Neiman played by Miles Teller, a student defined by his studiousness, albeit in its extremes. This manifests itself as a bright and nervous optimism which is inevitably crushed by the heavy-handed cynicism of Terence Fletcher played by J. K. Simmons, music teacher and lead conductor of the famed Schaffer Studio Band.

Neiman’s persistence to impress Fletcher during his time at the Schaffer Conservatory of Music is symbolic of the purest ambition. The blood on the drumsticks, his swollen hands and his tired eyes all signs of the perseverance that encompasses him and makes him the most desperate student we have seen on-screen. His passion turns quickly into obsession, his talent turns into punishment. The only reward in sight is Fletcher’s approval - a gift rarely, if ever, given.

Chazelle looks at Election’s Tracy Flick and raises you Neiman in total defiance of the 90s on-screen student: in place of Flick’s constantly-sabotaged ambitious campaign as a way to mock and trivialise the student, Neiman’s real source of sabotage is his own desire for Fletcher’s validation. In creating such a clearly damning interpretation of the ultimate student, Chazelle finds the perfect response for Freedom Writers’ Brian Gelford who confidently tells Gruwell that “you can’t make someone want an education”: through Neiman, Chazelle shows how his siblings’ mockeries, the thrill of competition and sheer persistence makes him want an education.

It makes him want it so badly that he lets himself fall into Fletcher’s traps all over again: only to overpower his tactics and find his moment in the limelight. The student, subjected to the teacher’s berating, has learnt the ultimate lesson: maybe you’re better than the teacher.

From 1985 to 2015, from The Breakfast Club all the way to Whiplash, audiences find a way to connect with the student. Whether it’s the passion they show, or the apathy; whether it’s their desperation to be liked or their comfort in being alone, students on-screen are an echo of the systems that shape us. They document what the dominant perceptions of education are like in their time: from America’s hyper-fixation with the dumb quarterback (Election’s Paul Metzler) to the strong-headed but overlooked young girl (Freedom Writers’ Eva Benitez) to the ever-obedient yet incredibly isolated high-achiever (Whiplash’s Andrew Neiman), they have all been emblematic of a cultural phenomenon.

As we find ourselves halfway into the next ten years of students on-screen, I for one am excited by what we have begun to see in the 2020s: Netflix films like To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before, The Half of It, and even the controversial Sierra Burgess is a Loser all had main characters that defied the type-casting of the white American 90s student, but kept all the charm associated with the high-school genre. Movies like Bottoms have captured the essence of what a modern-day Tracy Flick would be up against whilst taking a similar position as Election in this decade’s pop culture history.

The student's portrayal on-screen is undeniably intertwined with the coming-of-age genre. It’s for this very reason, filmmakers should strive to tell the most authentic stories possible. Take the recent Didi from Sean Wang: his main reason for making the film was not seeing himself portrayed in films about growing-up. These past thirty years of students on-screen have shown us how powerful storytelling can be; shaping the attitudes towards education in their respective eras.

I’d love to hear if there’s been a film in your childhood that shaped the way you thought of school, or shows the student-teacher dynamic a little differently. For reviews of the films mentioned, you can check my Letterboxd.

Have seen so many clips of Freedom Writers on reels… you are extremely accurate in your scathing review of it - it’s only revolutionary if you live under a rock or are living in the year 2005.