Interview with Joshua Trigg: BIFA-nominated director of 'Satu: Year of the Rabbit'

I chatted with Josh about the beauty of Laos, the struggles of indie cinema and how lived experiences reflect on-screen

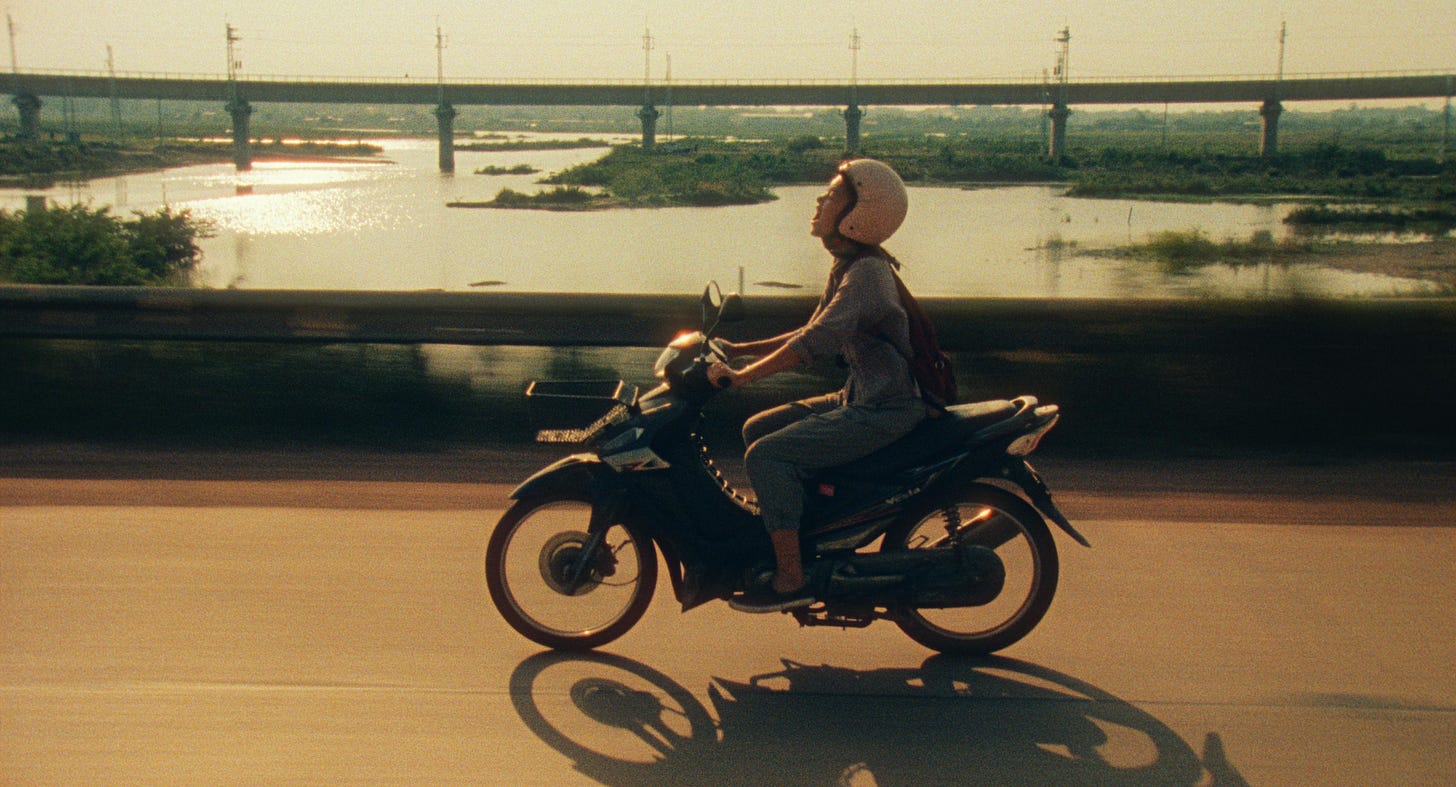

Earlier this year, I attended Sheffield’s Spirit of Independence Film Festival (read more about it here) and managed to catch Josh Trigg’s Satu: Year of the Rabbit - a debut that’s managed to catch the attention of BIFA with a recent nomination for the film.

Funded mostly by Josh himself during periods of quarantine thanks to the old pandemic, Satu is a labour of love and whilst its production was a minefield of unexpected spanners being thrown into the works of an ambitious cross-cultural production, it has emerged successful and as a testament to Trigg’s determination to see the project through.

I chatted with Josh last week, learning more about his journey to Satu and the time spent on set.

The Amateur’s Take: Obviously, you’ve seen my initial review of the film and it’s an understatement to say I enjoyed Satu, and I was really pleased to be able to catch it at Sheffield’s Spirit of Independence Film Festival. It seems like it has been quite a journey to get the film to the BIFA nomination level, congratulations on that, of course. You’ve also received some great acclaim on the other side of the world, with the Golden Shika award from Nara International Film Festival as well. Have you noticed a difference in Eastern and Western reception of the film? Why do you think that is?

Josh: It’s funny because I feel like there’s been no traction in the US. The script did better than the film over there, including Canada. In Europe and Asia, it’s doing well but in different ways. In Japan, they really love it, they already have an interest in Laos with their combined history. Through that, I think they have general intrigue because it feels impossible to make films in countries like that. I mean, I’ve been working in Asia for the past fifteen years and I’d love to make a film in Japan. But in Southeast Asia, I think the reality is that there’s just an interest in these slower stories, as opposed to the horrors and comedies that come out of the continent. In Europe, it’s ticking along as you’d imagine, with the perception of World Cinema.

The Amateur’s Take: It’s so true isn’t it - as the average cinema-goer, World Cinema seems so much harder to tap into for a more general audience and I don't think that's a comment on the audience. I think that's just a comment on what we've all collectively made World Cinema out to be, like this thing that you can't understand unless you’re clever enough or intellectual enough.

Josh: Yeah, sometimes I think we have so many films that don’t feel like film to me, with such crazy budgets like 200 million to make a new Iron Man film or something that’s its own beast in its own industry - that just doesn’t compute to me.

The Amateur’s Take: And on top of that, it feels like that’s made cinema super commodified, and made stories like Satu less accessible.

Josh: Yeah exactly, I’m sure tons of people are trying to find a way through to it and talking about it but on the flip side of that, I do think that audiences are surely bored of this by now because everything’s so overly advertised. I do feel like there’s more of an appetite for stories like this now and people are tired of advertisements. I’ve been working in the commercial side of filmmaking for fifteen years and I think they’re bored.

The Amateur’s Take: I do think people are getting apathetic towards the idea of watching the same narrative play out again and again. I think it helps a lot that the new generations are more and more online, allowing access to things that wouldn’t have been so easily achievable for previous generations.

Josh: Yeah, you can get all this online - it’ll all end up on the internet one day.

The Amateur’s Take: I wanted to also congratulate you on such a successful cross-cultural project. One of the things I’m constantly advocating for is the importance of these types of collaborations where you’ve actually worked with the people of Laos rather than just working around them. Having said that, I’m curious to hear why Laos became the home of Satu.

Josh: I’d just done a series of mini-docs for a brand in South East Asia, really people-focused stuff. This was in 2018 and we had a week off and just drove north, via this really scary mountain range that was still being built into a road. Massive adventure trip and it was so beautiful and green and luscious when we went there. Of course with Satu, we could only shoot in the dry season so a lot of that natural beauty isn’t in the film, but it still looks beautiful on film. I just fell in love with that space with beautiful little mountains all framed by these arches of stunning architecture.

The Amateur’s Take: It was undeniable, how mesmerising the beauty was on screen. I commend you for making something so beautiful through such a trying time. I’ve read that due to budget constraints and production in the wake of the pandemic’s disruption, combined with being an independent film, the production of Satu felt exceptionally hard to navigate at times. Were there points you questioned seeing the shoot through, or were uncertain whether you’d succeed in creating a finished feature?

Josh: So many times. I don’t even know where to begin. We nearly pulled the plug the night before we flew out. We had spent such a long time refurbishing a new lens that ended up getting left on the tube and then recovered - it was a whole thing and I was waiting for another problem to happen at that point, the finances were a mess thanks to my funding falling through. So within a week or so, I had to find 40 grand. Somehow we skirted through, 85% of it was funded by my commercial work and I came back from the shoot like 70 grand in debt which I only just finished paying off last week. Then during the shoot, we had the camera breaking down. Then everyone was ill at some point because the water was tainted in the town we were in - it was crazy. During filming, there was only one flight out every couple of months: sometimes it felt like I wasn’t getting out of there.

The Amateur’s Take: It feels like the making of the film deserved its own documentary!

Josh: Honestly, the crew were like family and I don’t think I want to do it that way, but we made it through.

The Amateur’s Take: Delving a little deeper into the story of Satu itself, I think you’ve crafted a tale of belonging through a lens that is often overlooked. Most coming-of-age stories are very Western-centric but through the backstory of our female lead character Bo, who delivers an insanely captivating performance, you break down the all-too-common misconception that coming-of-age stories are only for American teenagers. She comes from a household with an abusive father, the absence of a mother and a dream to be a photojournalist. On that last aspect, was there a specific inspiration for her being interested in such a specific career?

Josh: Well, my real father was a war photojournalist. He wasn’t a particularly nice person, with a lot of abuse in my childhood, and I don’t always want to pull from my experience when building a story but I think that’s a massive psychological explanation for this character. Pairing that with how I grew up in a very female household, I guess I’m more drawn to female characters and maybe that’s why she’s the main character. I think I saw both characters as different versions of me in my life, especially when I was writing it, so she could be a filter for my experiences. But about Bo, she’s in escapism mode, right? The photojournalism gives her something to view the world through and teaches her how to see the world in a different way which is what she teaches Satu as well. I’ve also been in photography for a long time, so there’s a lot of motivation behind that decision.

The Amateur’s Take: It’s so nice to hear that a project that you were so clearly connected to and was such an important part of your life, has parts of you in it in such subtle ways. Not to stereotype, but it challenges that very ‘film-bro’ mentality that the director shouldn’t be in the film - I don’t subscribe to that idea at all.

Josh: I’ve seen this being spoken about a lot, more than I did in the past and I’m really curious about it. I don’t think it really matters but it is true that if you work off of lived experiences you’ll make a story in a very honest way. At the end of the day, what makes a film have more depth to it, is what’s behind it.

The Amateur’s Take: If we want to diversify our storytelling, we have to do it through lived experience right?

Josh: That’s the most authentic way to do it, but I don’t think that you would watch Satu and think that it’s about my life.

The Amateur’s Take: I don’t think it comes across like that no, but being set in a different country helps.

Josh: Yeah of course, and also stories are universal too. Satu translates well across cultures, I think.

The Amateur’s Take: I agree. Now, the whole aim of The Amateur’s Take is to try and champion amateurism in cinema, to try and encourage everyone to watch a film to enjoy their own unique experience. So on that note, Satu is an independent film of course from humble beginnings. I think you'll have a great insight on this, but why do you think we need the amateur filmmaker? Why are the smaller stories so important and what is it about them that's so crucial?

Josh: At the end of the day, indie cinema is the most important. I don’t call Iron Man cinema. It’s commercialism versus art. My mum is a great storyteller, I get that talent from her. I think without people like that, cinema becomes nepotistic. All the same money in the same places and they keep making the same things again and again. So the only way to break out of something like that is through amateurism and for projects like that, you don’t even need that much of the money that they use to make these massive films. But there’s also the problem of how these institutions that support indie projects are so hard to get funding from - I’ve never gotten funding from places like that. We need stories from people with different financial backgrounds and different cultures - all for the love of storytelling. And even that is totally subjective, you can tell the story however you want to. Even on your phone; building your everyday phone into your storytelling makes everyone an amateur. Whatever you do, you usually have to make money in some other way to fund the story you really want to tell. There’s a real importance in not losing sight of the goal you have.

The Amateur’s Take: I think you’re right, and that translates across all aspects of the industry - in front of the camera, behind the camera, in front of a triple-monitor editing set-up: it’s always applicable. You’re saying everyone is an amateur and maybe this makes the next question a little redundant but let’s see: was there a turning point when you started to feel like a professional filmmaker? What's the difference between an amateur and an expert?

Josh: I think it’s just in the mind, right?

The Amateur’s Take: Sure, but would you call yourself a professional now?

Josh: I think there’s a division between the commercial world and the creative world. The commercial makes you feel accomplished the more time you put it: I remember co-directing with someone else for a brand and they said we were filmmakers and film directors, which felt quite uncomfortable and not true. The only time I feel like I could be a professional with Satu for example, is when I have provided a service. The film isn’t even officially released yet and people haven’t gone to the cinema to buy a ticket outside of the festival; if that happens, then I’d feel somewhat professional. The industry is so messy that I don’t think I’ll ever fully stop feeling like an amateur. It’s always been at the forefront of my mind for sure. It takes some people ages to fulfil their project; some debuts happen at 45 years old. If you do feel like a professional in creative filmmaking - maybe that’s a problem. That’s when you start making Iron Man films.

The Amateur’s Take: I love that Iron Man’s cropped up three times now.

Josh: It’s funny because my sister is a dancer actually and was in Wicked, she’s in this world of more mainstream filmmaking which feels a lot less like cinema, and more like movies. And that side of the film is just so different to what I know, so different to Satu. I was so specific about the way I wanted to make Satu: people asked me to go digital, to do it somewhere else, to delay it and I said no. But regardless of whether it is commercial or not, you’re there to make something.

The Amateur’s Take: As a viewer, I like the idea, that if you’re a professional and you see it as a job, it can be a problem, especially in creative fields. Incredibly insightful. Final question, and thanks so much for some great answers so far. The other important angle I try to take here at The Amateur’s Take is diversity’s benefit to both the creator and the viewer. There is such a cultural richness in Satu, it’s undeniable. For most viewers, this will be their first exposure to a film shot in Laos, with a local cast and crew. There’s that famous Bong Joon-Ho quote about overcoming the one-inch barrier of subtitles, but as someone who’s worked in Southeast Asia for so long with so much depth, why would you encourage and recommend Western audiences to explore Asian cinema?

Josh: It’s so diverse to start with, and it massively challenges European concepts of film. I started falling in love with Korean cinema after Oldboy - that just changed my life. I’ve always been drawn to Asian media, I was the 15-year-old who was teaching myself Japanese, you know. It’s the visuals of it, right? These locations enrich the stories and if you want to be massively thrilled and surprised, Asian cinema is the shout. It is such a change from the normal structures of Hollywood and change the endings - like you think the film’s over and then all the characters die out of nowhere. It’s an incredibly rich history as well, with countries like Cambodia that have less of it now after the Khmer Rouge destroyed the country, but they still love cinema in all its formats. They love film in Thailand, young people are crazy about it. No one had shot anything on 16mm in Laos since the 60s, not until Satu.

The Amateur’s Take: It’s great that you had early exposure to World Cinema and it’s carried through into your projects, I’m excited for what comes next. Thanks so much for bringing Satu to us and congratulations on your BIFA nomination again!

It's very easy to see the glamour of film, but not the time-consuming labour and arduous challenges that come along with it. But also, as someone that champions Asian cinema and is from Southeast Asia, this article meant a lot to me! Great read as usual, and I think you ask excellent questions about the nature of cinema as an art form and the importance of stories outside the Hollywood-centric view :). Will have to check this out if I ever get the chance.